This article was first published in the National Review on April 21, 2023. Click Here to read the original article.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has forced hard choices on the U.S. and its allies in determining how to respond to such unprovoked and unwarranted aggression. The U.S. is doing its part, but Japan, a member of the G-7 and the third-largest economy in the world, has dragged its feet and stopped at mere rhetoric. A more robust Japanese response is necessary to support Ukraine, beginning with cutting off trade with Russia’s staunch ally, the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Iran is one of the few countries helping the Russian military kill innocent Ukrainian civilians and continue its invasion. For months now, the Russian military has used Iranian drones, and it is also seeking to acquire Iranian missiles, according to the Biden administration. And Japan appears to recognize the importance of Iranian weaponry to Russian forces: Earlier this month, Deputy Foreign Minister Shigeo Yamada reportedly asked Tehran “to stop supplying weapons to Russia.”

This was a ridiculous request. Iran has no intention of voluntarily slowing its cooperation with Moscow; it must be compelled to do so. Unfortunately, Japan has shown no appetite for concrete steps to punish Iran. It is the only member of the G-7 that has failed to apply any sanctions whatsoever on Iranian officials or entities since September, and both money and commercial products are flowing from Tokyo to Tehran — helping to prolong the war and encourage Iran’s malign behavior.

In 2022, Japanese general trading company Sojitz was fined more than $5 million by the U.S. Treasury Department for purchasing 64,000 tons of Iranian high-density polyethylene resin, which the Biden administration said “conferred significant economic benefits to Iran and undermined broad U.S. sanctions specifically targeting Iran’s petrochemical sector, a major source of revenue generation for the Government of Iran.” Later in the year, United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI) published evidence that Iran-backed Hezbollah is using communications equipment manufactured by Japan’s Icom Inc., which has another firm acting as its “official representative in Iran.”

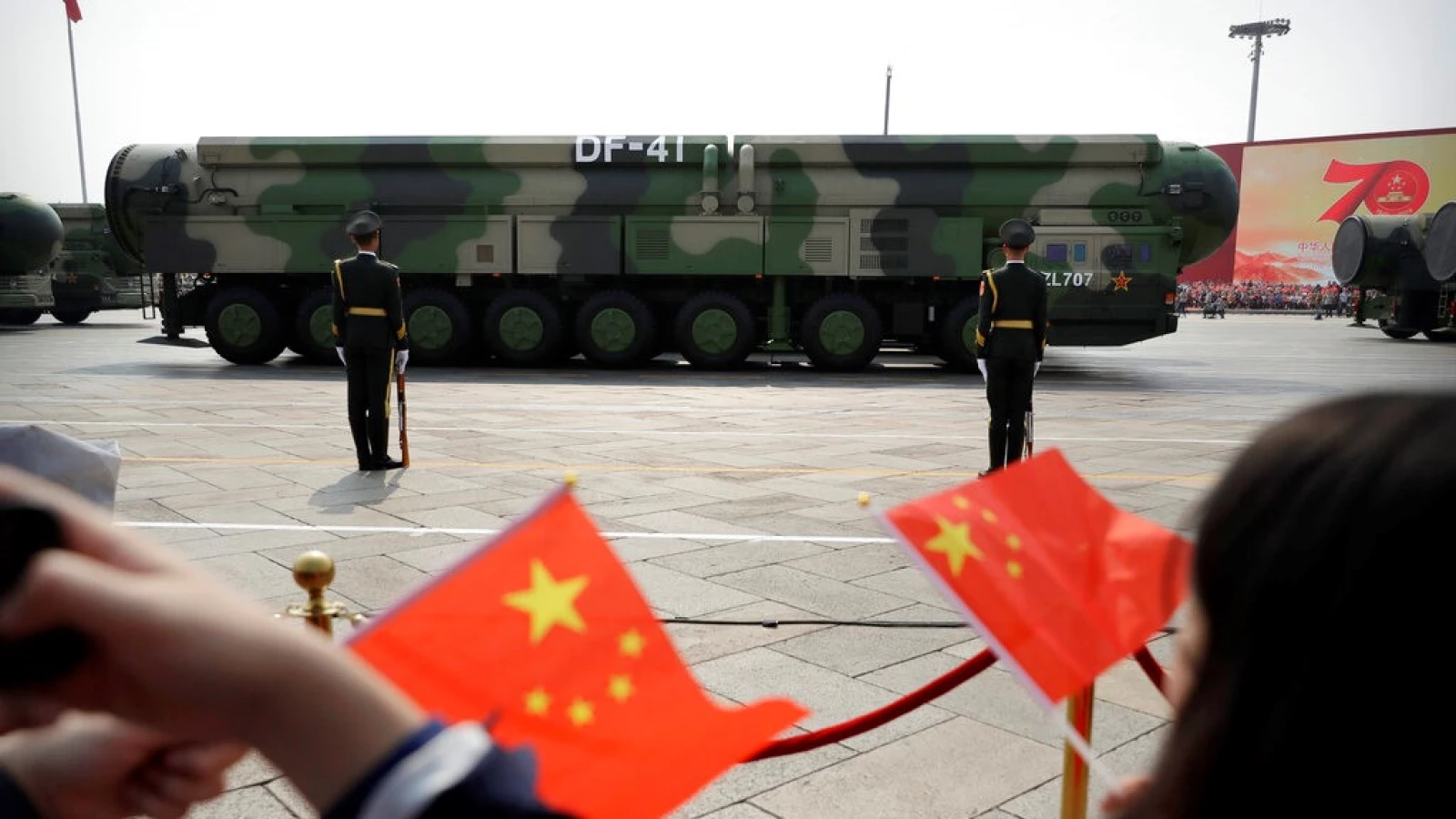

More recently, UANI uncovered evidence that Japanese defense firm Fujikura — which has contracts to support the Japanese Self-Defense Forces — is simultaneously engaged in the Iranian market as an approved vendor of several sanction-designated and state-owned entities, including some linked to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Japanese businesses also appear to be selling commercial products to companies in China that source components and software found in Iranian drones.

These commercial ties should be as unacceptable to the U.S. as the purchase of Iranian oil, which Japan has done without since May 2019. Japan should suspend its trade relationship with Tehran and, like the United States, force businesses worldwide to choose between doing business in Iran or Japan. After all, trade between Japan and Iran, directly and indirectly, supports Vladimir Putin’s war machine.

Suspending trade with Iran, as Japan’s allies and partners have already done, is the least that Prime Minister Fumio Kishida can do to support Ukraine given his country’s continued reliance on Russian energy.

If Japan does so, Prime Minister Kishida will demonstrate that he is taking Japan into a new era of global leadership. He has already signaled a willingness to take political risks in ways that his predecessors did not by becoming the first prime minister to attend a NATO summit, doubling Japan’s military budget, and agreeing to “take on new roles” in the Indo-Pacific, according to Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Prime Minister Kishida will also demonstrate that Japan is unafraid of using its substantial economic leverage to further international peace and security, drawing it closer to the U.S. and Europe and creating a stark contrast with malign states like China and Russia. Japan should adopt a version of the Magnitsky Act to more easily impose economic sanctions on individuals and entities suspected of human-rights violations.

Japan must recognize that it can have a tremendous impact on the war by targeting Iran for its role in supplying weaponry to Russia, and it need not wait until it hosts the next G-7 meeting in May to do so. If Japan addresses its ties with Tehran in the right way, it will create opportunities for a more confident and assertive nation to lead on the world stage. But if it addresses them in the wrong way, it will show that for all its economic strength, it is not yet confident enough to help direct world affairs.