By Ambassador John Bolton

This article was first published in the National Review, on January 5th, 2022. Click Here to read the original article.

Among the many unwelcome legacies of Donald Trump’s random walk through foreign and defense policy during his presidency, the resurgence of isolationism and know-nothingism in the Republican Party is among the most distasteful and dangerous. Isolationism has never entirely disappeared from the Republican Party’s fringes, and the Democrats’ leftist marches are perennial habitats for this virus. Trump, however, fostered a toxic environment within which the virus spread.

Isolationism comes in many forms. Like all national-security tags (e.g., “realism,” “liberal internationalism,” and “neoconservatism”), the label obscures more than it reveals and is worsened when paired with “internationalism,” its presumed opposite, as if to embrace all foreign-policy thinking. Ultimately, artificial conceptual classifications in foreign affairs, and attempts to define precisely who is or is not an isolationist, or who is best described by which bumper sticker, amount to no more than arid scholasticism. Besides, today’s isolationists are aware enough politically to deny the title even when it fits perfectly.

Taxonomy, although omnipresent in current discourse, is far less important than understanding isolationism’s core impulse: believing that the outside world matters little to America and that its problems can generally be ignored. Obviously, not all foreign events affect us equally or even significantly, but U.S. policy-makers cannot simply shrug off the broader world, which is isolationism’s default position. Debating what constitutes national-security interests is always legitimate, but too many contemporary politicians are unable or unwilling to do so. Accordingly, isolationism’s real definition resembles Justice Potter Stewart’s test for hard-core pornography: “I know it when I see it.”

I. The History

The isolationist virus thrives on a fictional history of America, ironically one largely crafted by liberal historians aspiring to lionize Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt. In this narrative, the United States rested peacefully alone, protected from foreign travails by broad oceans, until Wilson and Roosevelt dragged nativists kicking and screaming into the radiance of internationalism (and, later, globalism), a move the isolationists are now trying to reverse.

Actually, America was never as isolated or isolationist as some contend. At the outset, the U.S. abjured European conflicts to guard its independence and fragile unity against foreign meddling. In a critical but usually overlooked passage from his 1796 Farewell Address, George Washington wrote, “If we remain one people, . . . the period is not far off when we may defy material injury from external annoyance; . . . when belligerent nations . . . will not lightly hazard the giving us provocation; when we may choose peace or war, as our interest guided by justice shall counsel.” Washington’s advice was prudence, not blindness.

Our history, with some notable exceptions, reflects the sustained, successful pursuit of national interests and values, to the dismay of those, home and abroad, who share neither. America’s innovative capitalism drove us across the world seeking competitive advantage, complicating and interconnecting the world because it suited us. The United States prevailed repeatedly in Schumpeter’s gale of creative destruction, enormously benefitting our citizens, not to mention untold numbers of foreigners. Backed by the American Revolution’s financier, Robert Morris, the Empress of China kicked things off, sailing for China just months after the 1783 Treaty of Paris confirmed our independence. Nor were we content with private commerce. John Adams fought the naval Quasi-War against French privateers in 1798–1800, and, from 1801, Thomas Jefferson fought the Barbary pirates in North Africa because Europeans were unwilling to do so, preferring to pay tributes and ransoms. We created the Navy’s first Pacific Squadron in 1821, with a major battle in Sumatra in 1831; the South Atlantic Squadron in 1826; and the East India Squadron in 1835. We sailed Commodore Perry’s Black Fleet into Tokyo Harbor in 1853 to open trade with Japan.

Our attentions and energies were always substantially focused abroad, and we often butted heads with greater powers or dealt with them. Before the United States even consolidated the Paris Treaty’s boundaries, Jefferson’s 1803 Louisiana Purchase from France nearly doubled the country’s size, hardly the mark of stay-at-homers. We fought a second war against the U.K. in 1812, reaffirming the 1783 result, and so tellingly defeated the British at New Orleans that all Europe took note. On we went, purchasing Florida from Spain in 1819; promulgating the Monroe Doctrine in 1823 and thereby telling Europe “hands off” the Western Hemisphere; inventing “Baltimore clippers,” the world’s fastest oceangoing ships; and annexing the Republic of Texas in 1845. Splitting disputed lands with London in 1846, we picked up the Oregon Territory. Defeating Mexico in 1846–48 added America’s southwest, and the 1853 Gadsden Purchase consolidated the southern border. Even the Civil War barely slowed us down, as we purchased Alaska from Russia’s czar in 1867.

America’s massive post–Civil War industrialization then produced comparable growth in international trade, reinforcing concerns for protecting our interests worldwide. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge embodied key elements of “the shift from continental to hemispheric defense,” in Colin Dueck’s phrase. This included annexing Hawaii in 1898 and significantly growing Navy budgets. Lodge worried about British designs on Hawaii and was appalled at Grover Cleveland’s acceptance of a U.K. firm’s laying telegraph cable from Hawaii to our Pacific coast rather than assisting a U.S. company. Lodge advocated “protecting American interests and advancing them everywhere and at all times. . . . I would take and hold the outworks, as we now hold the citadel, of American power.”

The 1898 Spanish–American War, following the probably accidental sinking of the USS Maine in Havana’s harbor, resulted in America’s controlling the Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, and Cuba (temporarily). Theodore Roosevelt divided Colombia in 1903, making Panama independent, to build the long-imagined canal. He later visited his handiwork, the first president to travel outside America while in office. Having won the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize for settling the Russo–Japanese War, he dispatched the Great White Fleet (16 battleships plus accompanying escorts) around the globe in 1907, all actions consistent with the works of Alfred Thayer Mahan, the world’s greatest sea-power theorist.

Covering just over a century postindependence, even this Calvin Coolidge–length history hardly reveals a country sitting contentedly by the fireside, knitting. World War I, however, undeniably brought to the fore Wilson’s vision, which asserted that America’s principal wartime goal was to “make the world safe for democracy.” Theodore Roosevelt responded characteristically: “First and foremost, we are to make the world safe for ourselves. This is our primary interest. This is our war, America’s war.” He argued further, “We cannot at this time make any distinction between the German people and the German rulers, for the German people stand solidly behind their rulers, and until they separate from their rulers, they earn our enmity.”

Congress’s post-war rejection of Wilson’s hallowed Treaty of Versailles and League of Nations was evidence less of isolationism than of his arrogance. The Senate comprised roughly three factions: Democrats supporting the treaty as written; Republicans led by Lodge supporting ratification, with reservations to protect U.S. sovereignty; and the Irreconcilables, totally resistant. Outright ratification, opposed by Lodge Republicans and Irreconcilables, lacked the required two-thirds Senate vote. Wilson doomed the treaty by refusing to allow Democrats to back Lodge’s reservations, making it the first peace treaty ever rejected by the Senate.

II. Some Lessons for Policy-Makers

A century separates us from Versailles, but the central conceptual national-security lessons of U.S. history were already evident then to anyone paying attention. After World War II, as America moved from hemispheric to worldwide defense, those lessons were debated and tested. Washington and its allies created a partial, contingent, imperfect world order, based often on our unilateral exercise of power, initially to withstand the Soviet-led communist challenge. This world order, although changing constantly, persists to this day. If we were to abandon this order, such as it is, as isolationists seemingly want, who would fill the gaps? Certainly not the United Nations or other international organizations. There are only two possibilities: adversaries such as China and Russia, or no one, creating anarchy, nature’s default condition. There is no rational argument that either alternative would be better for us.

Liberal internationalists argue that multilateralism, embodied in institutions such as the U.N. and the International Criminal Court under the rubric of “the rules-based international order,” is the answer. I have written previously in these pages (“A World without Rules,” February 7, 2022) why the “rules-based international order” is nonsense, and earlier on the U.N. and the ICC. The arguments need no repetition here, for despite their many faults, isolationists rightly oppose the Left’s theological obsession with multilateralism.

Ironically, a variant on liberal internationalism is generally called “neoconservatism.” Neocons have a harder edge than liberals, agreeing on many goals with plain conservatives but following a different logic. With Democrats, they advocate a “liberal world order,” contending it has long been our policy. This is surely false. Lodge and the Republican Roosevelt were classic national-interest advocates, blocking and tackling for America, not for abstractions (although if they had one, it was “America” itself). Isolationists caricature neocon views as those of the Republican establishment, which is also false, and an issue for later rebuttal. If foreign-policy debates were only between neocons and Roosevelt-Lodge Republicans, I would be a happy man.

Instead of abstractions, the pursuit of U.S. interests remains the foundation of conservative national-security policy. These interests are concrete, including defending our territory and its people; guarding our trade and commercial interests, including access to natural resources; and providing reliable protection for our allies. Declaring that nearly everything important involves “national security” debases the language: If everything implicates national security, then nothing does, and reason is lost. Of course, higher aspirations are noble, and appealing to the virtues is an inevitable aspect of political leadership. In recent history, America’s higher aspirations fused seamlessly with hard national interests, as in the 20th century’s world wars, two hot and one cold. But conservatives stress that our resources must be concentrated first on our interests, which are expansive.

The May 1947 speech of undersecretary of state Dean Acheson to Mississippi’s Delta Council admirably illustrates this clear-eyed approach. Acheson chose to make the Marshall Plan’s first public preview to an association of farmers and agricultural businesses in Cleveland, Miss., because of the audience’s self-interest. World War II had devastated U.S. farmers’ foreign markets, and Marshall aid could be critical in reviving them. Acheson began by saying, “You who live and work in this rich agricultural region . . . must derive a certain satisfaction from the fact that the greatest affairs of state never get very far from the soil.” He knew that business was business for the Delta’s residents, and abstractions such as internationalism or isolationism meant little to them. If he could convince Mississippi’s Delta farmers that the Marshall Plan was in America’s interest, who else could remain unmoved?

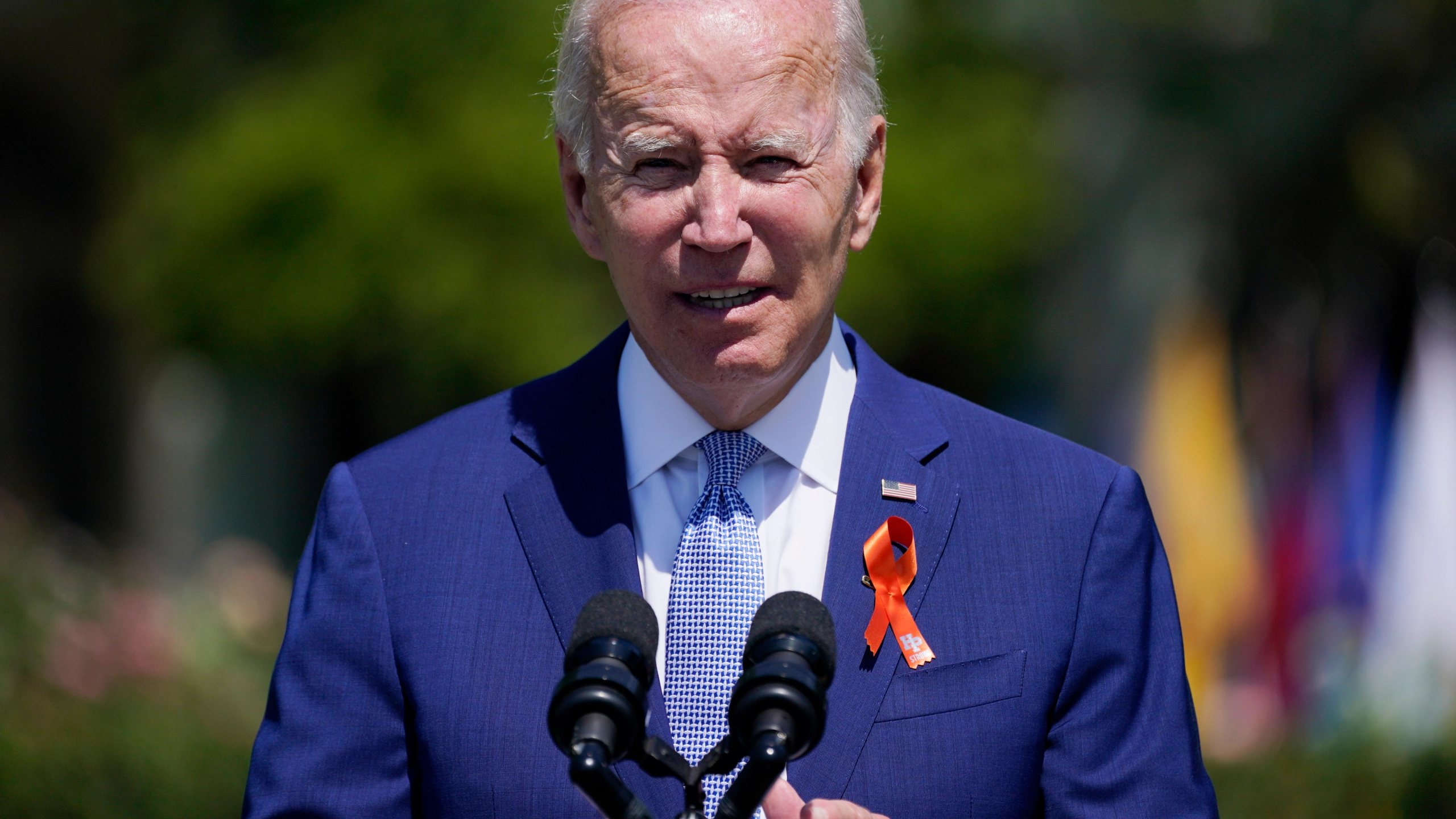

Unlike isolationists’ breezy dismissal of foreign affairs, deriving an interests-based U.S. foreign policy requires hard intellectual work, assessing priorities and constructing strategies to provide resources to achieve them. This is a source of strength, not weakness, as the timing and location of Acheson’s speech indicate. Making the economic and politico-military case is neither irrelevant (pace the neocons) nor unworthy of serious treatment (pace the typical isolationist sneering). Analysis and logic are critical both to implement sound policy and to ensure durable political support. Indeed, today, the principal threat to continued U.S. popular backing for Ukraine is President Biden’s failure to delineate his ultimate objectives and how to achieve them.

Calculating geostrategic advantage is often, with good reason, compared to playing chess. Statesmanship is not simply a “for want of a nail” litany, but a chain of logic and evidence. Isolationist politicians rarely engage in geostrategic analysis, preferring instead to intone their own mantras (“End the endless wars”), deploy non sequiturs (“What about the southern border?”), or make personal attacks against opponents. If they were ever to address geostrategy, that alone would be progress, albeit unlikely given the personalities involved.

Most foreign-policy decisions are made at the margin, day to day, like chess moves: Why act here? Why now? Nonetheless, however inconsequential a particular national-security decision point may seem, it didn’t arise without a history, and it will have future ramifications. Both the history and the future ramifications must be measured against American objectives and capabilities. Failure to grasp history or experience, and having no vision of future threats, increases the risk of catastrophic failure, which will present no good options. Prior decisions do not inevitably dictate subsequent ones, but whether the current decision is bold or timid, it will be a better decision if it reflects understandings of its origins and consequences. Unfortunately, isolationists play chess one move at a time, having no larger strategy, and their failures become incalculably costlier.

Analysis and persuasion must be sustained over time to ensure domestic support. Ronald Reagan, for example, stressed that America’s safety and prosperity depend on a strong international posture, and likewise that a forward position abroad rests on a strong economy and society. His “peace through strength” legacy echoed the Roman adage Si vis pacem, para bellum (If you want peace, prepare for war), and it still represents the best rebuttal to the isolationists.

III. Applying the Lessons

Which brings us to today, when damage from the isolationist virus is already evident on many levels, starting with America’s retreat from Afghanistan, a blundering, bipartisan flight from reality. This totally unforced error, the epitome of Trumpian isolationism (and generic Democratic weakness), reflects disdain for the U.S. interests sacrificed. Among its consequences are (1) losing a critical surveillance post and staging ground against terrorism inside Afghanistan, and nuclear-proliferation threats from bordering Iran and Pakistan; (2) again exposing innocent American civilians to terrorist attacks emanating from Afghanistan, 9/11-style; (3) creating a power vacuum in central Asia that will be filled by China, Russia, terrorists, or all three; (4) lacerating the credibility of American commitments worldwide, especially with NATO allies who followed our post-9/11 lead, in NATO’s largest deployment in history; and, by the way, (5) sacrificing the Afghan people to renewed Taliban (and other extremist) misrule.

Trump’s first, most egregious mistake was negotiating with terrorists while excluding Afghanistan’s legitimate elected government, which we helped create at such cost in U.S. lives and treasure. The negotiations fatally crippled the Kabul regime, as Trump signaled he did not intend to hold the Taliban to their commitments any more than the Taliban intended to honor them (which there was never the slightest reason to believe anyway). In turn, Biden’s decision (entirely his own) to follow Trump’s fatally flawed deal reflects the Democratic Party’s Mahatma Gandhi wing. In July 1940, Gandhi advised the British about the Nazis: “If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourself, man, woman and child, to be slaughtered . . .” By departing Afghanistan, we effectively wrote its people the same message. And dealing with renewed terrorist threats emanating from Afghanistan will weigh heavily on the next president.

America’s role in Iraq has a long, controversial history. Today’s dominant view is that the 2003 decision to overthrow Saddam Hussein was mistaken. Rather than rehashing the question here, consider the key point of Barack Obama’s 2011 withdrawal of all U.S. and coalition forces under the pretext of being unable to negotiate a satisfactory status-of-forces agreement (SOFA) with Baghdad. That decision, clearly a sharp break with past policy, did not anticipate the consequences of upending ten years of America’s in-country presence (and foreshadowed the Trump/Biden retreat from Afghanistan).

Withdrawal was clearly wrong, as proven when Obama reversed himself in 2014, returning U.S. forces (without a SOFA) to oppose ISIS’s terrorist threat, which had metastasized from its previous al-Qaeda incarnation. Not only did America’s departure contribute to destabilizing a visibly wobbly post-Saddam Iraqi state, but our return, based significantly on mistaken views of Iran, materially empowered Tehran’s control over Iraqi-Shiite militia, which was clearly foreseeable. Thus, even our ultimate destruction of the ISIS territorial caliphate effectively strengthened the ayatollahs’ hand in Iraq and still failed to eradicate the ISIS threat. As Michael Gordon argues in his book Degrade and Destroy, Obama’s return to Iraq conceded that his “paradigm for ending the ‘forever wars’ had collapsed,” a lesson that isolationists (of Left and Right) have obdurately refused to learn.

U.S. policy disagreements on Iran reflect the pre-Trump world, with Republicans almost unanimously taking a hard line against Tehran’s nuclear-weapons and ballistic-missile programs; its own terrorist activities and support for terrorist groups worldwide; and its malign regional conventional military operations. Trump left Obama’s misbegotten 2015 nuclear deal in May 2018, reimposing American economic sanctions (although not enforcing them effectively). Biden has spent nearly two years slavishly searching for the right combination of concessions to get back into the deal, so far unsuccessfully. Meanwhile, Iran and its proxies continue to attack and threaten Americans in the Middle East and globally, unworried about a vigorous U.S. response. Intense, continuing, near-revolutionary opposition to the ayatollahs’ regime has now apparently awakened some administration officials, but Biden’s position remains merely that it is currently inconvenient to focus on reentering the deal. Once those distracting demonstrations end, Biden’s negotiators will be back at it. Absent a contrary sign from Trump, who has not (as yet) changed his view, Republicans of all stripes will continue adamantly rejecting the deal, a rare piece of good news.

Strategically, Russia’s unprovoked aggression against Ukraine is now America’s most urgent priority, with enormous global consequences if we get it wrong. We need to ensure that Ukraine does not become a second Afghanistan (and Taiwan a third); instead, isolationists concentrate on ignoring both Ukraine’s history and the implications of the war and its outcome. Unfortunately, the isolationist virus is having its most visible success on Ukraine, stemming almost entirely from the “Russia collusion” hysteria, Trump’s personal fixation with Ukraine as a purported nest of anti-Trump activity in both the 2016 and 2020 elections, and his resulting scorn for the country and its leaders. It is otherwise inconceivable that Democratic and Republican positions on the Kremlin, enduring through and after the Cold War, could be so thoroughly reversed. Happily, the extent of Trump’s damage among Republicans remains slight, but the media focus on Ukraine, hoping to anathematize all Republicans via Trump, is oxygen for isolationists.

When Volodymyr Zelensky spoke to Congress on December 21, some members weren’t paying attention or simply didn’t attend. They missed a compelling speech, directly confronting their “arguments” against U.S. assistance to Ukraine. Typically, the isolationists advance no strategic perspective, arguing instead against providing resources that should be used domestically (also a favorite argument of progressive Democrats) or arguing that we should pay more attention to our border with Mexico. Both of these arguments, of course, are non sequiturs, since failing to achieve certain objectives does not excuse failing to meet others. Zelensky rightly stressed that our aid was not “charity,” given America’s manifest interest in deterring or defeating aggression in regions critically important to Washington. As George H. W. Bush said in 1990 after Iraq invaded its southern neighbor: “This will not stand, this aggression against Kuwait.”

European peace and security have been cornerstones of American policy since 1945, for NATO members but also for countries whose independence and territorial integrity are critical to bordering and nearby NATO allies. George W. Bush was correct to propose fast-tracking NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia in 2008, and French and German opposition was a tragic historical mistake. Finland and Sweden, abandoning decades of neutrality that they maintained during the Cold War and even before, have now concluded that their security rests on joining NATO, showing more vision than isolationists who still can’t do their strategic arithmetic. Trump was hostile to NATO generally, as are his acolytes. Some argue that he was a necessary “disrupter” of complacency among European countries, and complacency there certainly was. But his disruption was not Schumpeterian, not aimed at improving NATO, but simply destructive. Vladimir Putin would have warmly welcomed more of the same from Trump’s second term, as Trump did to NATO what he did to Afghanistan.

Progressives have also opined on Ukraine, urging negotiations with Moscow in an October 2022 letter to Biden. Their missive raised inevitable comparisons to Neville Chamberlain’s characterization of Hitler’s 1938 annexation of the Sudetenland as “a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing.” Progressives quickly disavowed their letter’s timing, but none resiled from its substance. It was a classic Washington gaffe: saying exactly what they thought, just at an inconvenient time.

The progressives discerned Biden’s evident fears and uncertainties about his objectives in Ukraine. His lack of resolve has impaired both his policy’s execution and its domestic support. He has wilted under Putin’s threats and posturing — limiting, conditioning, and hesitating to provide needed assistance, ignoring Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s March 2022 comment that Putin has been “moving his forces into a wood chipper.” Thus, while America and NATO are degrading Russia’s military without a single U.S. casualty so far, a morganatic coalition of Left and Right isolationists nonetheless poses a considerable threat to thwarting Moscow’s Ukraine aggression.

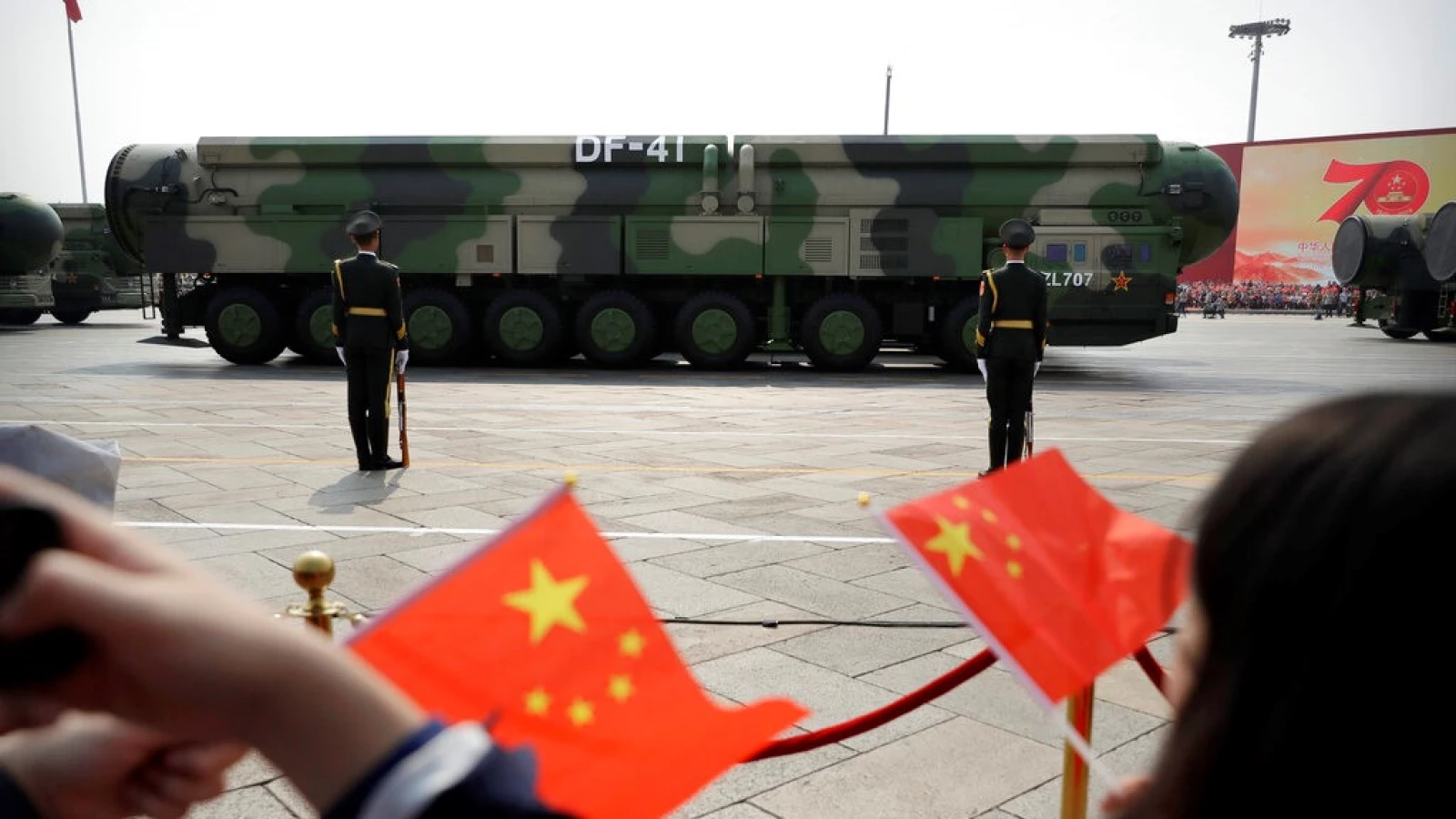

Notwithstanding the Ukraine war’s urgency, the breadth of China’s threat throughout this century in economic, political, and military terms, while existential, is still hard for many in the West to absorb. Although Beijing’s immediate focus is hegemony over Taiwan and other points along its periphery, its long-term objectives, manifested, for example, in the Belt and Road Initiative’s economic reach, include dominance over Latin America and Europe and ultimately global hegemony. Moreover, the growing Beijing–Moscow geostrategic entente is actually strengthened by the Ukraine war, entirely to China’s advantage, as its needy junior partner sees its military humiliated. North Korea, China’s geographic adjunct (and whose progress toward deliverable nuclear weapons the Biden administration has done precious little to stop), and Iran in the Middle East increasingly seem parts of a broader coalition directly threatening America and the global West.

The truly worldwide nature of China’s challenge precludes extended discussion here, but its emerging implications for the isolationist virus are noteworthy. Precisely because of the enormity of Beijing’s menace, some quasi-isolationists argue that crises elsewhere in the world (such as Ukraine, or Iran’s terrorist threats and potential acquisition of a nuclear weapon) are not significant enough, and that our resources are too limited, to risk distracting us from the main chance. This fantasy fails in many respects, but it may attract domestic support from those afraid to expose themselves as total isolationists, allowing them to write off the rest of the world under the guise of opposing China. They could maintain this pretext until the threat immanentizes and only then find it inconvenient to defend, say, Taiwan (never a Trump favorite), or ultimately anything else. Obviously, by then it will be too late to reverse the adverse consequences of having retreated elsewhere. A “China-only” foreign policy is isolationism’s version of John Ehrlichman’s “modified limited hangout”; however tantalizing, it won’t work any better now than the original did during Watergate.

IV. Tomorrow

America’s 2024 presidential campaigns, already under way, provide an excellent occasion for the necessary debate on isolationism, certainly for Republicans and conservatives, and even among Democrats if they are up to it. Since cashing in the illusory “peace dividend” at the Cold War’s end in 1991, U.S. and allied defense spending has been wholly inadequate. Prudent fiscal policy undoubtedly requires reducing federal deficits and the national debt, so the need for major defense increases means slashing unnecessary domestic spending even further. That budget exercise will pose difficult political challenges, but there is nothing better than a presidential election to uncover capable leaders. As Theodore Roosevelt said about World War I, “If we have the smallest power to learn by experience, let us face the damage done by our la-mentable failure to prepare in the past, so that we may learn the need to prepare for the future.”

The right Republican 2024 presidential nominee will stress bolstering existing alliances such as NATO; launching, enlarging, and expanding the scope of Indo–Pacific alliances; and taking advantage of the Middle East’s tectonic geopolitical changes to broaden Israel’s acceptance and strengthen partnerships against Iran’s malign activities. These alliances are not burdens for the United States but potential force multipliers, and they should be analyzed and evaluated as such. Undoubtedly, effective alliances also require that allies shoulder their responsibilities, lest isolationists, following Trump’s approach, deploy any failure to do so destructively against the very concept of collective-defense structures. Many NATO members still do not seem to be on the road to meeting the alliance’s 2014 Cardiff commitments to spend 2 percent of their GDP on defense matters, something that conservatives can insist on with no fear of ceding ground to NATO opponents. And while enhancing collective-defense organizations, we should carefully avoid the short-term temptation presented even by sound allies, and otherwise sound Republicans, to endorse international tribunals in lieu of national judicial systems to try war-related crimes.

In the Indo–Pacific, in contrast with the North Atlantic, conditions have never been comparable to the latter’s environment, where dense and extensive partnerships on politico-military and economic matters have flourished. China’s unprecedented assertiveness is now beginning to change the Indo–Pacific’s state of play, making it far more favorable to deeper and broader alliance projects. Moreover, important building blocks already exist through numerous U.S. bilateral alliances: the Asian Quad (India, Japan, Australia, and America), which is still far from NATO but nonetheless has considerable promise; and AUKUS, the trilateral partnership for the United Kingdom and the United States to produce nuclear-powered submarines with Australia. Creativity in developing new politico-military partnerships should be the priority, rather than looking only to create an Indo–Pacific NATO. Japan’s recent announcement that it will double its defense budget in five years, reaching the NATO target and making Japan’s military the world’s third-largest after America’s and China’s, shows what is at work in the region. And possibilities for economic or technological combinations with strategic significance also exist.

In the Middle East, the Abraham Accords are already bringing beneficial results, and more diplomatic recognition for Israel globally is undoubtedly coming. The turmoil in Iran is proceeding at its own pace, but overthrowing the ayatollahs, which is what the opposition is now advocating daily, is closer to hand than at any point since the Islamic Revolution seized power in 1979. Politico-military cooperation with Israel and like-minded Arab nations could go a long way to eliminating that regime, the greatest threat to peace and security in the region and beyond, and to denying Russia and China an ally they both need.

Beyond politics, serious strategic thinking about U.S. and allied defense budgets is essential. Some years back, U.S. military planners contemplated “full-spectrum dominance” in military affairs, a concept not much mentioned today, but still compelling. What threat along the spectrum from terrorism to conventional military weapons to offensive cyberspace capabilities to weapons of mass destruction (nuclear, biological, and chemical) does anyone seriously believe we can “isolate” ourselves from? Equally critically, over which parts of the weapons/combat spectrum are we willing to concede dominance to our adversaries? Let’s hear from isolationist opponents of defense-spending increases on these questions.

More prosaically, years of neglect have left us with inadequate supplies of existing weapons, demonstrated currently, for example, by the pressure to supply Ukraine with anti-tank Javelin missiles without completely depleting our own arsenals. New weapons systems to outpace China in all combat domains are critically needed, to say nothing of what we and our allies need elsewhere in the world. In particular, we need a dramatically expanded, modernized Navy to deter and contain China in the vast Pacific and Indian Ocean expanses. We have wasted decades by not expanding and improving our national missile-defense assets, a requirement defensive by definition and one that even isolationists should be willing to support. Dominance in space and cyberspace is essential not just for military purposes but to keep the homeland alive and functioning during crisis or conflict situations. And as was evident well before Covid but has been inescapable since, we need resilient, sustained American production capabilities for national-security requirements, with no reliance on insecure foreign supply chains.

This is nowhere near a complete list of what must be done not just to forestall isolationism but to correct long years of mistakenly believing that the Soviet Union’s collapse three decades ago had brought us to “the end of history” and a respite from strife. Republicans and conservatives, however, must urgently overcome the isolationist virus or there will be little hope of advancing the larger agenda. Now is the time to eradicate the virus politically, no matter how difficult the fight. Bring it on.

Mr. Bolton served as national-security adviser to President Donald Trump and as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations under President George W. Bush. He is the author of The Room Where It Happened.