This article appeared in The Daily News on April 7, 2021. Click here to view the original article.

By John Bolton

April 7, 2021

The recent conviction of seven prominent advocates of Hong Kong autonomy for participating in peaceful protests is yet another milestone in China’s campaign to bury freedom of speech and conscience. The authorities are suppressing not just student protesters, but the leaders of China’s most important freedom movement since Sun Yat-sen. Martin Lee, Jimmy Lai and others fought for decades to expand political freedoms, and now face lengthy jail terms.

How should the United States respond to these convictions, and the growing list of other acts of internal repression? Opening the March 18 Alaska encounter with senior Chinese diplomats, Secretary of State Antony Blinken raised Hong Kong as an issue concerning America. Shortly thereafter, the State Department’s 2020 human-rights report explicitly described extensive Chinese abuses, and the annual Hong Kong report to Congress confirmed that Beijing was systematically dismantling the territory’s separate status.

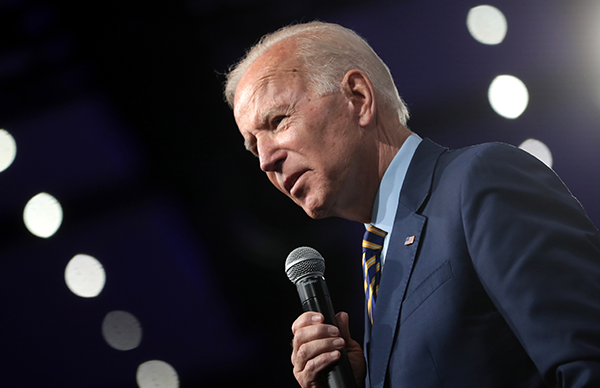

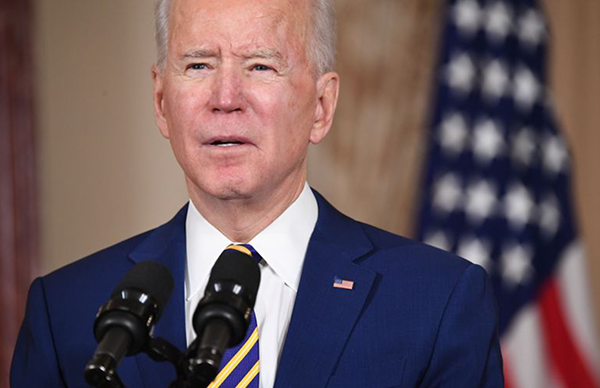

Recent administrations, including President Biden’s, have imposed economic sanctions on Chinese leaders. In retaliation, on Jan. 20, Beijing sanctioned 28 Americans (full disclosure: myself included), and later imposed travel bans on members of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom.

But is that it? Are salvos of economic sanctions effective, or are we Americans simply engaging in virtue signaling? Most importantly, how should human rights fit into U.S. national-security policy?

Despite considerable disagreement and confusion, a realistic approach is readily apparent. How China or other authoritarian states treat their own people speaks volumes about how they will treat us. Great-power authoritarians repress their citizens and threaten foreigners with hegemonic subordination. Rogue states like Iran and North Korea repress their citizens while seeking weapons of mass destruction and supporting international terrorism. None of them are trustworthy.

There are, of course, repressive regimes friendly to America. During World War II and the Cold War, we allied with such regimes, and often had their support in confrontations with regional authoritarian powers, as in the Middle East, which Jeane Kirkpatrick’s “Dictatorships and Double Standards” championed. This is neither immoral nor insincere, since Washington cannot cure all the world’s human-rights ills. Morality is boundless, whereas both state interests and material resources are finite.

The human-rights sins of friendly states have not threatened U.S. interests or values significantly, and are addressable through forceful but quiet diplomacy, not public breast-beating. Virtue signaling is for political show horses, but unbecoming for America.

As state policy, Washington’s opposition to Beijing’s repression or genocide is not abstract moralizing, but a legitimate concern for the implications of China’s domestic conduct on its behavior abroad. While not America’s job to mend the world’s ills, it is most certainly our job to protect ourselves. Thus, when China violates its 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration obligation to “a high degree of autonomy” for Hong Kong, it demonstrates graphically how it regards international treaties. It has not chosen to withdraw from the deal, but to violate it.

That demonstrates, not that we need further proof, Beijing’s true priorities. Chinese genocide against Uighurs, or repression of Falun Gong believers, Christians and Tibetan Buddhists, reveals how Beijing is prepared to resolve disputes with its near neighbors and beyond.

We should aggressively highlight China’s internal authoritarianism in our information statecraft, an aspect of U.S. diplomacy that needs enormous improvement. As during the Cold War, we need not fear a debate with China on human-rights issues. We should welcome it.

Rhetoric and individual sanctions alone, however, are not only inadequate but sometimes counterproductive, giving the appearance of “doing something,” when we are actually just being self-indulgent, not damaging our authoritarian adversaries.

Semiotic warfare should be left to academicians. The real way to make human-rights policy effective is by linking it with other bilateral priorities. How, for example, can we take trade agreements seriously when Beijing is prepared to sacrifice a choice economic asset like Hong Kong for overriding internal political considerations? Just how long will a Chinese pledge to buy more American soybeans last as compared to snuffing out internal dissent?

Economic complications were missing during the Cold War because U.S.-Soviet economic interaction was so limited. Of course, China’s massive penetration of Western economies makes it a far more dangerous adversary, but at the same time one more vulnerable to criticism and punishment for human-rights transgressions.

Washington still does not understand how to integrate human-rights issues effectively into foreign policy. Certainly, however, treating them in a silo separate from all other disputes with Beijing will only ensure their second-tier status. Advocates of an aggressive human-rights posture should recognize that trade-offs with other national-security priorities will be required. Accepting less-than-perfect outcomes means success, not defeat, because it means human rights are an integral part of U.S. policy, not an isolated, hot-house flower.